Five Key State Variations Every Foundation Should Know

Understanding where UPMIFA implementations diverge—and which states' laws apply to you

This is Part 2 of our three-part series on multi-state UPMIFA compliance. In Part 1, we explored why the "Uniform" Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act isn't actually uniform and why this matters for multi-state foundations. Today, we examine the five specific areas where state variations create compliance challenges—and help you determine which states' laws apply to your organization.

Where State Implementations Diverge

While 49 states have adopted UPMIFA, each made modifications reflecting local policy preferences. Here's where those differences create the most significant operational challenges for multi-state foundations:

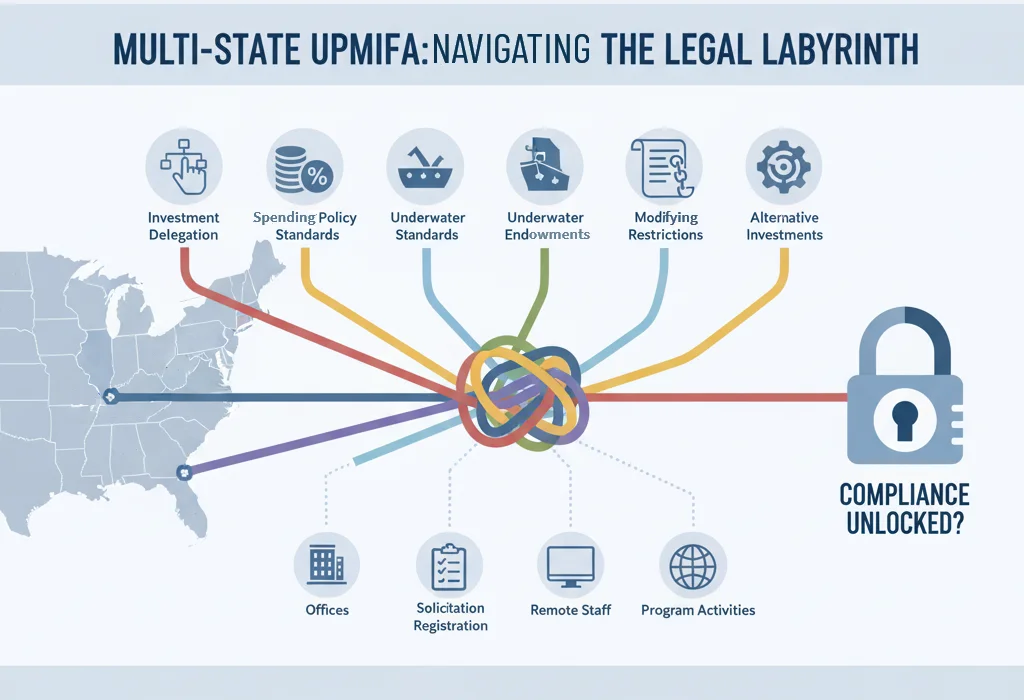

The six key areas where states diverge on UPMIFA implementation, and the four primary factors that create legal nexus requiring multi-state compliance

1. Investment Delegation Authority

UPMIFA's model act permits organizations to delegate investment management to external advisors—a critical provision given the complexity of modern portfolio management. This delegation framework is consistent across states.

What varies significantly is internal delegation—the authority of investment committees, officers, or staff to make decisions without returning to the full board for approval.

Why This Matters

The model UPMIFA is silent on internal delegation, explicitly deferring to each state's nonprofit corporation laws. As a result, states have taken different approaches:

- Some states require full board involvement for major investment decisions, even when day-to-day management is delegated to a committee. In these jurisdictions, an investment committee cannot independently change asset allocation, replace managers, or approve alternative investments without board approval.

- Other states permit broad committee autonomy within board-approved guidelines. Investment committees can make substantial decisions provided they operate within the investment policy statement parameters.

- Still others take a middle approach, requiring board approval for specific categories of investments (alternatives, for instance) or decisions above certain dollar thresholds.

The practical impact: If your foundation operates in multiple states, you must structure your governance to satisfy the most restrictive state in your footprint. An investment committee that functions autonomously in one state may be operating beyond its authority when the foundation has nexus in a more restrictive jurisdiction.

For foundations with quarterly board meetings, restrictive delegation rules can create operational friction and cause missed investment opportunities. The solution: understand your requirements across all relevant states and document delegation authority clearly.

2. Spending Policy Standards

UPMIFA's revolutionary change was eliminating the "historic dollar value" floor that prevented spending from underwater endowments. Instead, UPMIFA permits spending from any endowment—including those below their original gift value—provided the spending is prudent based on eight specific factors.

But "prudent" is inherently subjective. To provide clearer guidance, the model UPMIFA included an optional provision: a rebuttable presumption that spending exceeding 7% of a fund's fair market value (averaged over at least three years) is imprudent.

States split on this provision:

- Several states adopted the 7% presumption, including California, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah. In these states, you can spend more than 7%, but you must document extraordinary circumstances and demonstrate that such spending preserves the fund's purchasing power.

- Ohio took a different approach, creating a presumption of prudence for spending 5% or less—a safe harbor rather than a ceiling. Ohio doesn't establish a presumption for higher spending rates.

- Many states opted not to include any percentage threshold, relying entirely on the prudence standard and the eight factors without specific numerical guidance.

The practical impact: If you operate in a state with a 7% presumption, your spending policy must address this threshold even if your incorporation state has no such limit. You don't need to spend less than 7%, but exceeding it requires documented analysis of why such spending remains prudent under your specific circumstances.

The eight prudence factors apply everywhere. What varies is the framework for demonstrating prudence.

3. Spending from Underwater Endowments

One of UPMIFA's most important innovations was permitting continued spending from endowments that have fallen below their original gift value due to market conditions. Under the old UMIFA rules, underwater endowments were essentially frozen—a particular problem during the 2008-2009 financial crisis when many organizations desperately needed operational funding but couldn't access underwater endowments.

UPMIFA changed this by allowing spending based on prudence rather than absolute value thresholds. However, states vary in their documentation and notification requirements:

- All states require prudence analysis and board documentation when spending from underwater funds. This is universal.

- Some states have heightened documentation standards, requiring contemporaneous written analysis rather than after-the-fact documentation if challenged. California and New York, for instance, expect written board analysis at the time of the decision.

- A small number of states require notification to the state attorney general under specific circumstances. For example, New Hampshire and Texas require notification for smaller endowments (under $2 million in aggregate) when spending would cause funds to drop below historic dollar value.

Best Practice

Multi-state foundations must maintain comprehensive documentation of their prudence analysis for underwater spending decisions. The most stringent documentation standard in any relevant state becomes your operational requirement.

Quarterly underwater endowment monitoring is a best practice, with board or committee documentation of any spending decisions from underwater funds explicitly addressing the eight prudence factors.

4. Modifying or Releasing Donor Restrictions

Over time, donor restrictions can become outdated, impracticable, or even impossible to honor. A scholarship fund restricted to typewriter repair students has obvious problems in 2025. UPMIFA streamlined the process for addressing these situations.

The model act allows organizations to modify or release restrictions on funds meeting specific criteria without court approval:

- The fund must be relatively small (model act: under $25,000)

- The fund must be old (model act: more than 20 years)

- The organization must notify the state attorney general 60 days in advance

- The modified use must remain consistent with charitable purposes

States modified these thresholds substantially:

- California permits this process for funds under $100,000—four times the model act threshold

- Age requirements vary from 10 to 25 years depending on the state

- Some states adjusted the notification period from the model's 60 days

- A few states added requirements for attempting to contact living donors before using this process

The practical impact: When seeking to modify restrictions on an older, smaller fund, you must verify the specific thresholds in each relevant state jurisdiction. A fund qualifying for administrative release in California ($100K, 20 years) might not qualify in a state using the model act's $25K threshold.

Additionally, comply with the notification requirements of each state where you have nexus. If you operate in three states, you may need three attorney general notifications.

5. Alternative Investment Considerations

UPMIFA embraces modern portfolio theory, which often includes alternative investments like private equity, hedge funds, and real assets. The model act doesn't specifically address alternatives, applying the same prudence standard to all investment types.

States took varying approaches:

- Some states added explicit language authorizing alternative investments, providing comfort to boards considering these allocations. This explicit authorization was often added in response to state pension fund controversies over alternatives.

- A smaller number of states established enhanced due diligence requirements for alternatives, including specific analysis of liquidity, fees, correlation with existing holdings, and exit strategies.

- Most states remained silent, applying the general prudence standard without special provisions for alternatives.

The practical impact: Conservative boards in states without explicit authorization may hesitate on alternatives, even though the general prudence standard permits them. Conversely, foundations in states with enhanced due diligence requirements should apply those standards to all alternative allocations, regardless of where the investments are domiciled.

If you operate in any state with enhanced due diligence requirements, adopt those procedures for your entire alternative investment program. It's simpler to have one rigorous process than to track different standards by jurisdiction.

Which States' Laws Apply to Your Foundation?

Before addressing how to comply with multiple states' UPMIFA versions, you must determine which states' laws actually apply to your organization. This is often more extensive than foundations initially realize.

Legal nexus typically exists in states where your foundation:

- Is incorporated or legally organized - Your formation state always applies

- Is registered for charitable solicitation - Fundraising registration creates nexus and UPMIFA obligations. This is the nexus factor foundations most commonly overlook.

- Maintains offices or employs staff - Physical presence creates nexus, including remote staff working from their homes if you consider them based in that state

- Conducts substantial program activities - Even without staff, significant grant-making or program operations can create nexus

- Owns significant assets - Real property ownership clearly creates nexus; substantial investment accounts may as well, though this is less clear-cut

- Received endowment gifts with geographic restrictions - If a donor restricted a gift specifically to support programs in a particular state, that state likely has oversight interest

The Conservative Approach

If you're registered for charitable solicitation in a state, assume UPMIFA compliance obligations there. State attorneys general have jurisdiction over charitable assets, and UPMIFA provides the framework they apply in enforcement actions.

What typically doesn't matter: Where your investment custodian is located generally doesn't create UPMIFA nexus, though it may trigger other regulatory requirements like state securities registration.

A Common Surprise

Many foundations discover they have nexus in more states than expected. A California foundation that:

- Is incorporated in California

- Operates programs in Oregon and Washington

- Is registered for fundraising in California, Oregon, Washington, and Nevada

- Received a major gift restricted to Colorado environmental programs

...potentially has UPMIFA compliance obligations in five states, not just the three where it "operates."

What's Next

Now that you understand where state UPMIFA implementations diverge and which states' laws apply to your foundation, the question becomes: how do you build a governance structure that satisfies all relevant jurisdictions?

In Part 3 of this series, we'll provide a practical four-step framework for building multi-state compliance, identify common pitfalls to avoid, and give you specific action items you can implement immediately.

Uncertain About Your Multi-State Compliance?

Together Forward Capital works with foundations to identify which states' laws apply, assess current governance structures against all relevant requirements, and develop compliant frameworks that maintain investment flexibility.

Schedule a confidential consultation to discuss your foundation's specific situation.